Protecting Local Tech or Hurting Consumers?

Domestic Industry Protection vs. Global Competition

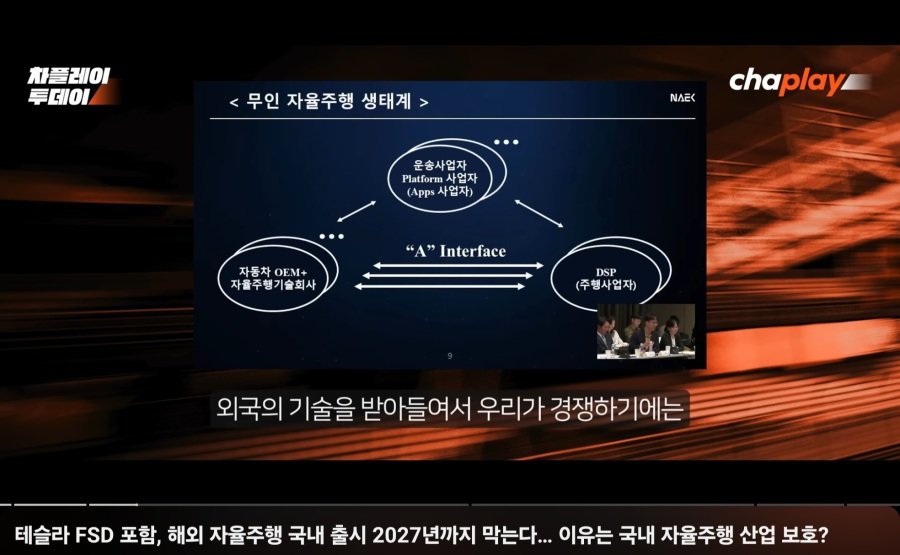

South Korea is currently grappling with a controversial proposal to block foreign autonomous vehicle (AV) services from entering its market until around 2027. This issue came to a head at a recent public forum on self-driving cars hosted by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. There, several industry experts urged the government to delay foreign entrants in order to protect and nurture domestic companies . Their argument is straightforward: Korean self-driving technology is lagging behind global leaders, and if companies like Google’s Waymo, Tesla, or China’s Baidu were allowed in now, local firms might be overwhelmed. By barring foreign AV companies for a few years, these experts believe Korean startups could catch up and establish themselves without immediate international competition .

Calls to Delay Foreign Autonomous Vehicles

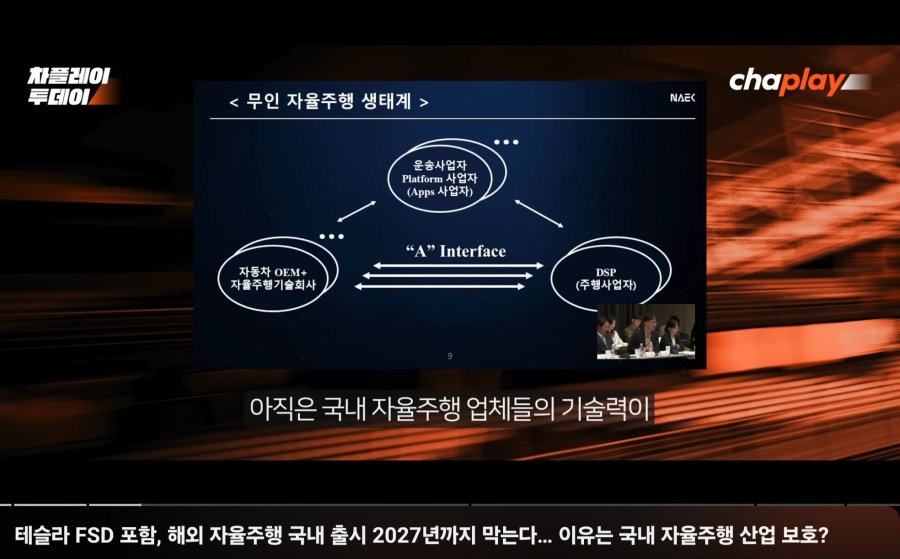

One proponent of this protective stance is Prof. Choi Joon-won of Seoul National University, who noted that Korea’s autonomous driving tech isn’t yet globally competitive. He argued that foreign AV firms have a significant head start, so giving Korean companies a 1–2 year grace period free from foreign rivals would help the local industry mature before facing direct competition . Similarly, Kim Ki-hyeok, CEO of Korean AV startup SWM.AI, made an impassioned plea citing China’s Pony.ai: what might take a Korean team 3 years to develop, Pony.ai achieved in 1 year. He warned that if advanced foreign tech floods in now, domestic firms “won’t survive”, and urged the government to hold off foreign players until the late-2027 timeframe, by which point he expects Korean AV technology could be export-ready. In essence, these voices are calling for a temporary non-tariff barrier – a regulatory wall to keep out foreign autonomous cars – to shield nascent Korean players until they can stand on their own.

Innovation at Risk: “Galápagos Syndrome” Concerns

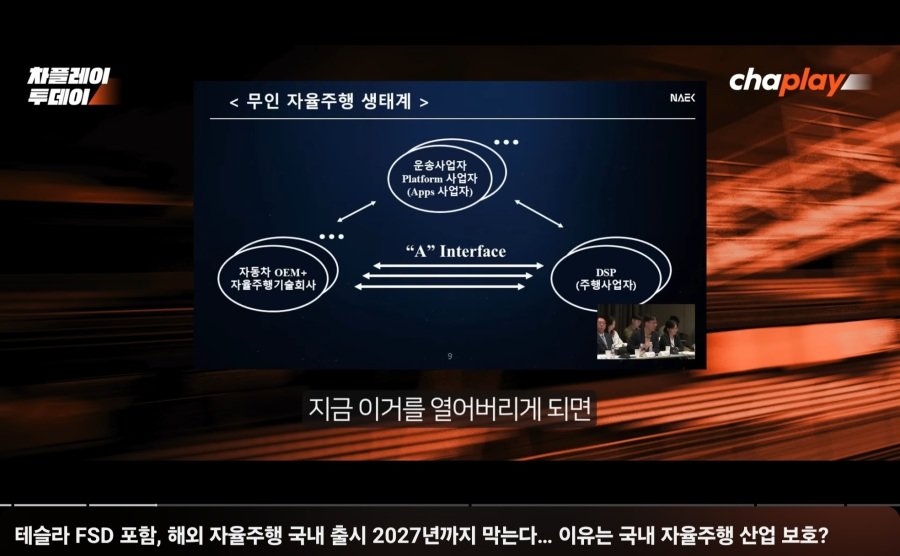

On the other side of the debate, many analysts and consumers are highly critical of such protectionism, warning it could backfire. Critics argue that isolating the Korean market for two more years may actually slow innovation and widen the gap with global leaders, not close it . If Korea’s self-driving companies operate in a sheltered domestic bubble, they risk falling victim to a “Galápagos syndrome” – developing technologies optimized only for Korea’s unique environment, but out of sync with global standards and trends. This term (originally used to describe Japan’s isolated mobile phone industry) implies that excessive market protection can make local tech an evolutionary dead-end, uncompetitive internationally. Past Korean industry experiences offer cautionary tales: policies of heavy market protection have at times stifled innovation and left Korean consumers with outdated options once the rest of the world moved on. The forum’s host even noted that unconditional protectionism in tech has historically led to “Galápagos”-like outcomes, where Korea fell behind and struggled to catch up later . In this case, blocking foreign AV services could deprive Korea of the catalyst of competition, potentially causing domestic firms to innovate more slowly while the world races ahead.

Consumer Choice and Market Consequences

Another major criticism is the impact on consumers. Preventing global AV leaders from operating in Korea means Korean consumers and cities might miss out on cutting-edge self-driving services available elsewhere. If Waymo robo-taxis or Tesla’s Full Self-Driving feature (widely used in other countries) are kept out, Koreans are essentially denied a choice – they must either use nascent local offerings or have none at all. Consumer advocates worry this infringes on consumer choice, leaving the public stuck with less mature or less proven domestic technologies for years. History suggests that Korean consumers ultimately benefit when global competition is allowed, as it raises quality and lowers prices. Over-protection can breed complacency among domestic firms, whereas competition would push them to improve faster. Critics point out that Korean tech firms have proven they can compete globally when forced to – for instance, Korean carmakers and smartphone makers thrived internationally once they faced foreign rivals head-on. Therefore, shielding autonomous vehicle companies behind regulatory walls might only delay the inevitable while hurting consumers in the interim.

Global Progress in Autonomous Driving

It’s also argued that Korea risks isolating itself just as autonomous driving leaps forward worldwide. In the United States, companies like Waymo and GM’s Cruise are already operating true driverless taxi services on public roads. California regulators recently approved 24/7 commercial robotaxi services in San Francisco for these companies , marking a major milestone – rider‐paid autonomous taxis are a reality today. Waymo launched the world’s first fully driverless ride-hailing service in Phoenix back in 2020 and remains a leader, having logged over 10 million autonomous miles . Cruise has also given thousands of rides in cities like San Francisco and Phoenix. In China, the autonomous driving sector is advancing at breakneck speed with strong government backing. Baidu’s Apollo Go robotaxi service has provided over 11 million rides, surpassing Waymo’s total rides, and is rapidly expanding to new cities and even overseas markets . Chinese AV startups like Pony.ai and WeRide, flush with funding and government support, are scaling up operations and even testing in the U.S. as they chase global leadership . Dozens of Chinese cities have introduced AV-friendly policies to encourage this growth . Even Japan is welcoming foreign autonomous tech rather than blocking it – for example, Alphabet’s Waymo has partnered with Tokyo’s largest taxi company and is beginning to test its self-driving cars on Tokyo streets with government cooperation . In short, the U.S., China, and even Japan are moving full steam ahead, integrating autonomous vehicles into real-world services. If Korea enforces a “foreign AV freeze” until 2027, it could find itself two years further behind these frontrunners when it finally opens the gates. The global autonomous race won’t pause for Korea, and catching up later could prove far more difficult if domestic players haven’t been pushed to match the Waymos and Baidus during the crucial developmental years.

A Look Back: The iPhone Launch Delay in Korea

Koreans don’t have to look far for a precedent of this kind of market isolation – the case of Apple’s iPhone is a famous example. In the late 2000s, while the iPhone was revolutionizing mobile markets worldwide, South Korea initially barred the iPhone and other foreign smartphones through a regulatory requirement. Specifically, all cell phones sold in Korea had to support a domestic software platform called WIPI (Wireless Internet Platform for Interoperability) – a standard no foreign phone used. This rule effectively blocked foreign-designed handsets like the iPhone from the Korean market . The ostensible goal was to protect the local mobile ecosystem (dominated by companies like Samsung and LG) from outside competition. The result, however, was that Korean consumers were unable to access the iPhone for over two years after its global debut, while the rest of the world moved ahead with app stores and touchscreen smartphones. By late 2008, Korean authorities faced reality: the WIPI mandate was a technological trade barrier holding the country back. After heated debate, the rule was dropped in 2009, with officials citing global trends and the need to widen consumer choice as reasons for the change  . Once the barrier fell, devices from Apple, RIM (BlackBerry), Nokia and others finally entered the Korean market, ushering in the modern smartphone era . In hindsight, the delay did no favors to Korean industry – domestic phonemakers had to compete with the iPhone eventually anyway, and Korean app developers and consumers had simply been left behind for a time. If anything, the protectionist policy nearly caused a “Galápagos” effect in Korea’s mobile sector, which was developing peculiar homegrown services that didn’t align with global app ecosystems. Only when Korea opened up did its tech sector fully innovate and integrate with world standards. Today, Korean consumers enjoy the fruits of global competition (Samsung and Apple fiercely compete in Korea), and even Korean firms like Samsung learned to thrive through competition, not by avoiding it.

Korea’s Autonomous Driving Status Quo

Proponents of the 2027 foreign AV ban might argue that Korea’s current autonomous driving industry is still in an early, fragile stage, deserving some incubation. Indeed, South Korea’s self-driving services are currently limited in scope – mostly pilot programs in controlled environments. For example, startup SWM.AI operates the country’s first licensed robotaxi service in a section of Seoul (Gangnam), but it’s on a very small scale. Over ~10 months, SWM’s pilot completed about 5,000 rides with zero accidents, an impressive proof-of-concept, yet a tiny number of rides compared to U.S. or Chinese services  . Most other domestic efforts are still in testing phases or confined to specific smart-city zones and designated test beds. In short, Korea has no widespread commercial AV service yet – no equivalent to hailing a Waymo One taxi in Phoenix or a Baidu Apollo Go in Beijing. This reality underscores why officials and local CEOs are anxious about an influx of foreign competitors. If Waymo or Cruise were allowed to launch in Seoul tomorrow, they would be entering a market where local offerings are still basically in beta. The worry is that consumers (and even investors) would flock to the proven foreign option, possibly squeezing the life out of Korea’s startups before they truly get off the ground.

Balancing Protection and Progress

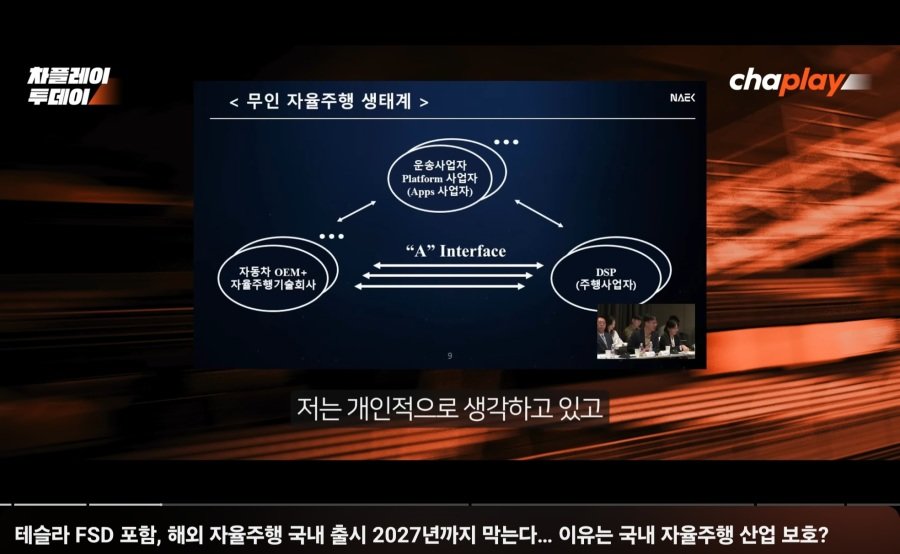

The challenge for South Korea is finding the right balance between nurturing its nascent autonomous driving industry and embracing healthy competition. A short grace period for domestic companies, as suggested, might indeed provide some breathing room to refine their technology. Optimistically, by 2027 Korean firms like SWM, Hyundai’s Motional, or others could develop self-driving systems robust enough to compete globally, thereby protecting high-tech jobs and even creating export opportunities. However, the risk is that protection becomes procrastination. If Korea’s AV sector is effectively sealed off from international competition for too long, it may grow complacent or technologically insular. The global autonomous vehicle industry is evolving through iterative learning, vast amounts of driving data, and cross-border investment – all of which could bypass Korea if foreign players and technologies are kept out. As one commentator noted, shielding an industry can inadvertently “freeze” it in time, while the rest of the world forges ahead . Korean policy makers also must consider the consumer perspective: Korean drivers and passengers deserve access to the best and safest innovations, whether homegrown or imported. Over-protectionist policies have in the past been shown to limit consumer choice and delay access to new technologies – the WIPI/iPhone episode is a case in point  .

Conclusion: Lessons from the Past, Eyes on the Future

South Korea’s debate over foreign autonomous vehicles is essentially a tug-of-war between short-term industrial policy and long-term global competitiveness. The arguments for a temporary barrier until 2027 reflect legitimate concerns about fledgling Korean companies in a fierce worldwide race. But South Korea’s own history in tech suggests that integration, not isolation, ultimately yields innovation and growth. The world will not wait for Korea: American and Chinese firms are accumulating experience and data by the day, and even countries like Japan are partnering to bring in the best technologies . If Korean companies are to truly become world-class competitors, they likely need to face world-class competition – perhaps not all at once, but sooner rather than later. In the long run, the goal should be for Korean autonomous vehicles to not only catch up to Waymo or Baidu, but to overtake them. That won’t happen if they’re racing on a closed track at home. As the critics of the 2027 ban emphasize, Korea must avoid a self-imposed tech island and instead find ways to encourage innovation (through R&D support, partnerships, smart regulation) without depriving consumers of global advancements. The experience with smartphones a decade ago is a cautionary tale: Korea initially shut out the iPhone to protect local phones, but in doing so it arguably delayed the progress of its own mobile ecosystem  . Eventually Korea opened up, and its tech industry adapted and thrived on the world stage. The autonomous driving sector may chart a similar course – a period of intense domestic development, but ultimately an embrace of global competition. For now, Korean regulators have a tough decision: how to foster a homegrown autonomous driving industry without repeating the mistakes of over-protection. The key will be ensuring that any measures taken truly strengthen domestic innovation, rather than simply erecting barriers. In an era of rapid technological change, Korea’s best bet might be to run faster – not to put up a wall and catch its breath.

Sources: Recent commentary on Korea’s autonomous vehicle policy ; reports on Korea’s past smartphone protectionism and its repeal  ; U.S. and China robotaxi deployment data (Waymo, Cruise, Baidu)  ; Japanese partnership with Waymo ; and Korean domestic AV pilot information  .

'IT & Tech 정보' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 히데토시 가토리(Hidetoshi Katori) 연구자 프로필 학력 나이 고향 노벨물리학상 (0) | 2025.10.07 |

|---|---|

| Wave of Cyberattacks in South Korea Sparks National Security Alarm (0) | 2025.09.29 |

| 화태규전 (華泰矽電) – 반도체 설계 회사 개요 및 현황 (0) | 2025.09.28 |

| 달러 패권과 부채 유지의 새로운 경로로서의 스테이블코인 (0) | 2025.09.27 |

| 의식, 현실, 통제: 이츠학 벤토브의 이론과 CIA 연구, 현대 폭로 사례 (0) | 2025.09.25 |