Introduction

In late 2025, South Korea was rocked by its largest-ever e-commerce data breach – a cyber incident at Coupang that exposed sensitive information from over 33 million customer accounts . The breach itself was alarming enough, but an even more explosive controversy soon followed. Korea’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) became entangled in the response, sparking a heated dispute between the spy agency and Coupang over who directed the investigation and whether proper authorities were bypassed. Accusations flew in parliamentary hearings, with Coupang’s interim CEO Harold Rogers claiming he acted on NIS orders, and the NIS angrily denying any “meddling” in the probe  . Lawmakers have censured Coupang for its handling of the leak – and even threatened perjury charges against Rogers – while the NIS now faces renewed scrutiny for potential overreach.

This report provides a detailed timeline of the breach and ensuing clash, dissects the conflicting claims (including whether the NIS told Coupang not to involve the police), profiles Coupang’s acting CEO and his controversial testimony, reviews the NIS’s history of overstepping its authority, and summarizes the political fallout in Seoul’s National Assembly. Finally, it analyzes who is more likely misrepresenting the facts and explores the legal and political ramifications if South Korea’s intelligence service indeed pressured a private company to sideline law enforcement. For American readers, the saga carries broader implications about cybersecurity breaches, institutional transparency, and corporate responsibility – drawing parallels to how such issues might be handled in the United States.

Timeline: From Massive Breach to Spy Agency Showdown

June–November 2025: Coupang’s data systems were quietly compromised starting around June 24, 2025, via overseas servers, but the company remained unaware for months . On November 18, Coupang finally discovered the breach, which would prove to be the worst in South Korea in over a decade  . Initial investigations pointed to an insider-turned-hacker: a former Coupang employee (reportedly a Chinese national) who had abused an active authentication key to siphon customer data .

November 29, 2025: Coupang publicly acknowledged the breach, revealing that personal information from about 33.7 million customer accounts had been exposed . The stolen data included names, email addresses, phone numbers, delivery addresses and purchase histories – though the company stressed that no payment or password information was taken . The scale of the breach – affecting roughly two-thirds of South Korea’s population – immediately drew outrage and government attention.

November 30 – Early December: Under intense public pressure, Coupang’s then-CEO Park Dae-jun issued a public apology on November 30  and began coordinating with authorities. However, even in these early stages, there was friction over transparency. Coupang initially downplayed the incident as a “data exposure” of just 4,500 users on Nov. 20, but regulators quickly ordered the company to correct its terminology to “data leak” and notify all affected users  . By the first week of December, the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) had stepped in, forcing Coupang to re-issue notices to all 33.7 million customers, and to explicitly acknowledge the incident as a breach rather than a minor exposure  . This semantic correction was significant – under Korean law a “data breach” implies a serious security failure warranting heavier penalties, whereas an “exposure” suggests a milder, accidental leak .

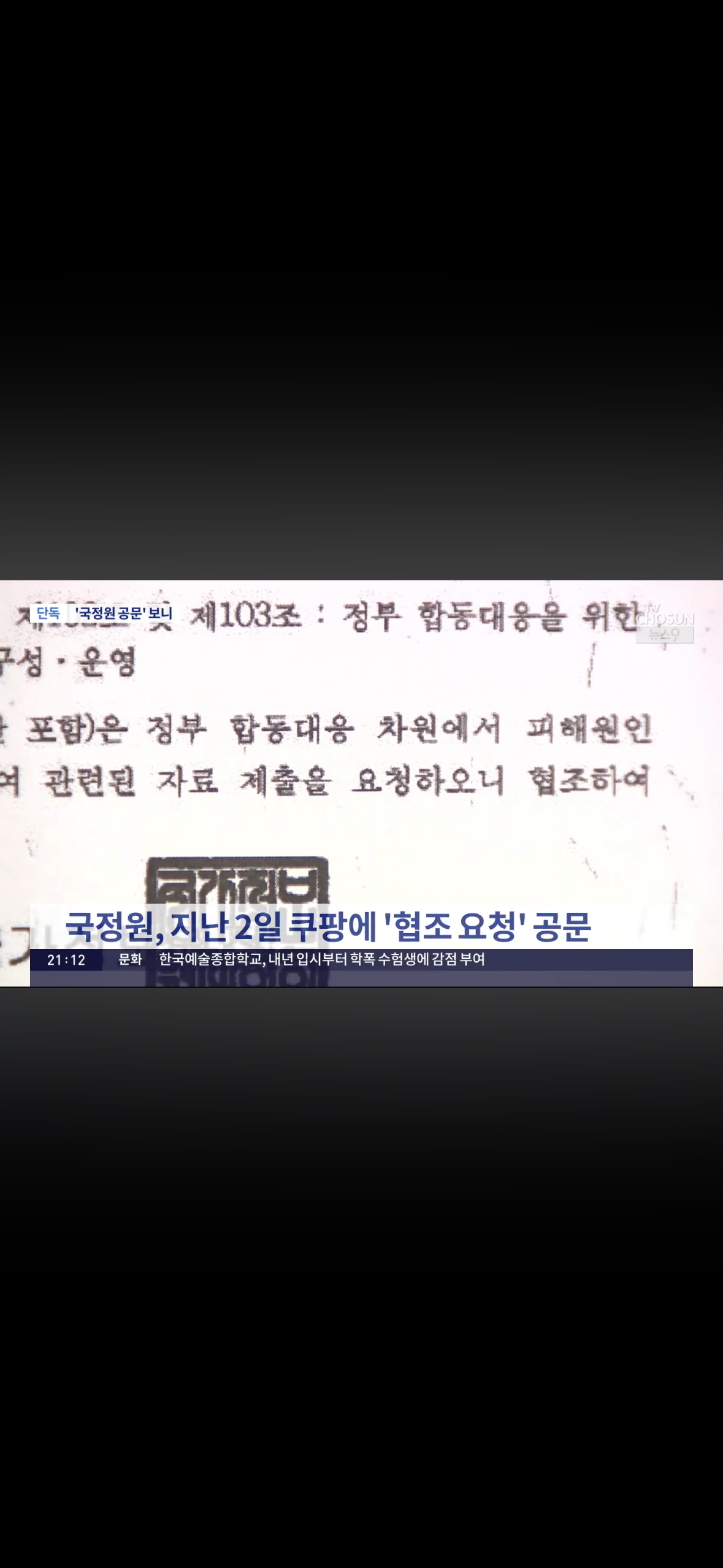

December 2, 2025: The plot thickened when South Korea’s National Intelligence Service sent an official letter to Coupang on December 2, effectively inserting itself into the case. Although the full contents of the NIS’s letter have not been made public, it formally put the spy agency on record as participating in the breach response. That same day, CEO Park Dae-jun was grilled in an emergency National Assembly session . Lawmakers pressed for answers on how the breach happened and why so much data was vulnerable. The NIS’s involvement was not yet widely known, but behind the scenes, the intelligence agency was gearing up its own inquiry. December 2 appears to mark the point when Coupang’s breach response shifted from a standard law enforcement matter to an intelligence-led operation.

Early to Mid-December: According to Coupang’s later statements, the company began closely cooperating with “government” agencies in the first half of December, following their guidance step by step. A timeline released by Coupang details a series of coordinated actions :

• December 9: The government (later acknowledged to mean the NIS) “suggested the company contact the person suspected of leaking data.” In other words, rather than immediately leaving the pursuit of the perpetrator to police, authorities advised Coupang to reach out directly to the suspected ex-employee . This is highly unusual; companies typically would hand such leads to the police.

• December 14: Coupang investigators met face-to-face with the suspect (reportedly in China, since the individual had left Korea) . The same day, Coupang says it reported the meeting’s outcome back to the government. By this point, the company had effectively become an arm of a covert investigation, operating under NIS direction rather than in tandem with police.

• December 15: Unbeknownst to the NIS, Coupang had already taken a critical step on its own – making a forensic copy of the suspect’s hard drive . (This detail would later become a point of contention, as the NIS claims it wasn’t even aware Coupang had imaged the drive until days later .)

• December 16: Coupang says it retrieved the suspect’s desktop computer and hard drive and submitted these devices to the government for analysis  . Essentially, Coupang’s team had secured key evidence (presumably by convincing the former employee to turn over hardware) and handed it directly to NIS personnel rather than to police investigators.

• December 17: The NIS officially made contact with Coupang’s team on this day, according to the agency’s account . At this point, the NIS learned that Coupang had already copied data from the suspect’s drive. The intelligence service maintains that during communications on Dec. 17, it “reiterated multiple times that Coupang should make a final judgment” on whether to engage the suspect  – distancing itself from directly ordering the company’s actions. Nonetheless, by now the NIS was clearly deeply involved.

• December 18: In a dramatic turn, Coupang recovered the suspect’s laptop from a river near the company’s Seoul offices – apparently the individual had attempted to dispose of this device by dumping it in water . Coupang’s investigators, following “government orders,” recorded a forensic image of the waterlogged laptop’s data and then handed the physical device over to authorities . This step suggests an effort to preserve evidence under NIS guidance, again prior to any police involvement.

• December 21 (Sunday): Only at this stage – after the suspect had been contacted and all devices secured – did the operation loop in law enforcement. “The government allowed Coupang to submit evidence and testimonies to the police on Sunday,” Dec. 21 . In other words, for nearly two weeks the NIS oversaw a parallel investigation while the police were kept in the dark. Indeed, the Seoul Metropolitan Police later confirmed that “there had been no prior contact or consultations with Coupang before Sunday” December 21 . The police cyber bureau only then received the suspect’s hardware and evidence, and began their own forensic examination of the laptop that Coupang belatedly turned over .

• December 23: At the NIS’s request, Coupang gave an additional private briefing on Dec. 23 to government officials about all the investigative steps taken and evidence obtained . This indicates that even after the police were finally engaged, the NIS was still directing information flow and debriefing Coupang separately.

• December 25: Coupang went public with the preliminary results of its internal (or NIS-directed) investigation. In a press release on Christmas Day, the company dropped a bombshell claim: while the hacker accessed 33 million accounts, he allegedly only saved data from about 3,000 of those accounts, then deleted it, and “no customer data was shared with any third party”  . In effect, Coupang asserted that the damage was far less than feared – only 3,000 customers had their info actually stolen in a usable form, and even that was not disseminated further. To mollify users, Coupang simultaneously announced a compensation package (50,000 won, or ~$35, in shopping vouchers per affected user)  . This announcement, coming before the official government investigation had concluded, infuriated Korean authorities and lawmakers. The Ministry of Science and ICT immediately blasted Coupang’s disclosure as a “unilateral statement” not vetted by the joint public-private investigation team  . The ministry lodged a formal complaint, emphasizing that any data from 33 million users being accessed is a grave matter, and expressing “regret and frustration” that Coupang acted on its own timeline .

Late December – Fallout Intensifies: By the final week of December, the breach had escalated into a full-blown public scandal, with daily developments:

• December 26: Coupang doubled down on its narrative. In a detailed press release, it “denied claims that [it] independently looked into its recent data breach” without oversight, and insisted it “followed the government’s investigative order and closely cooperated with the authorities” throughout . The company even published a timeline of its cooperation (as outlined above) to prove it was acting under government direction, not conducting a rogue “self-investigation” . This was clearly aimed at rebutting criticism that Coupang had tried to play lone cowboy. However, officials remained unconvinced. That same day, Deputy Prime Minister and ICT Minister Bae Kyung-hoon publicly reaffirmed that “more than 33 million personal records, including names and email addresses, had been leaked”, directly contradicting Coupang’s 3,000-account story  . Bae cited findings from the government-police joint investigation team that was now finally in gear, pointedly saying he could “not agree” with Coupang’s downplayed figures . He even noted that delivery addresses and order information were also likely leaked for those tens of millions – implying the breach’s impact was broader than Coupang admitted . Bae criticized Coupang for announcing unverified results “without coordination” while an official probe was ongoing, calling it a cause for “serious concern” .

• December 29: South Korea’s National Assembly prepared for a high-profile hearing to grill Coupang’s leadership and government officials. Tensions were high, especially after Coupang’s perceived defiance of Korean regulators in favor of updating U.S. investors first. (Notably, Coupang had filed its internal probe results with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to comply with U.S. disclosure rules, even as Korean authorities protested the findings  . This created an impression that Coupang cared more about its Wall Street stock price than Korean public accountability.) Lawmakers from multiple committees planned a rare joint hearing on December 30, to address not just the data leak but a laundry list of Coupang controversies (from unfair trade practices to worker safety) that the breach had brought to the fore . Coupang’s founder and CEO, Bom Kim, had been summoned and pressured to attend in person. When word came that Bom Kim (a Korean-American billionaire) would not appear – it would be his eighth no-show at a Korean parliamentary hearing  – Assembly members were livid. “Chairman Bom Kim’s claim that he cannot attend because he is overseas is, in my view, an act that truly mocks the public and delivers despair to global investors,” fumed Rep. Choi Hyung-du, noting that even U.S. tech titans like Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos have testified when called . The National Assembly moved to file a legal complaint against Bom Kim and other absent executives under a law compelling witnesses to comply with parliamentary subpoenas . This set the stage for a dramatic hearing with Bom Kim’s surrogate – interim CEO Harold Rogers – in the hot seat.

• December 30: The joint parliamentary hearing unfolded in Seoul and quickly became combative. Rogers, who had only been installed as acting CEO weeks earlier after Park Dae-jun’s resignation, faced a barrage of questions for hours. (Park had resigned on Dec. 10, taking responsibility for the breach, and Coupang’s U.S.-based Chief Administrative Officer Harold Rogers was appointed interim Korea CEO  .) The Dec. 30 hearing turned into political theater at times: Rogers caused a stir by initially refusing to use the National Assembly’s official interpreter, insisting on using his own personal interpreter instead  . This led to a shouting match over translation accuracy and was viewed as disrespectful by lawmakers. Once substantive questioning resumed, Rogers maintained that “the government agency instructed us, and we did what [it] told us to do”, directly implicating the NIS . He testified under oath that “the investigation was not internal but conducted over several weeks under government instructions,” pushing back on the “self-investigation” accusation . Rogers further asserted that it was the NIS that repeatedly asked Coupang to contact the suspect – something Coupang says it was initially reluctant to do – effectively portraying the firm as simply following NIS orders in reaching out to the hacker  . These claims were met with immediate, vehement denials from the NIS (which had representatives observing the hearing). Within hours, the NIS issued an official statement branding Rogers’s testimony as “clearly false” and asking the Assembly to charge him with perjury  . The spy agency flatly stated that “besides requesting materials, it has never ordered, instructed nor permitted any actions by Coupang” and “is not in a position to take such action” . It also refuted Rogers point-by-point on specifics: denying that it gave any direct order to meet the suspect (saying it told Coupang the final decision was theirs) , noting that Coupang copied the hard drive before NIS involvement (implying Coupang acted on its own initiative) , and denying Rogers’s claim that the NIS kept a copy of the drive or provided an extra copy to Coupang . NIS officials bristled that Rogers’s remarks “undermine the credibility” of the state agency, and took the extraordinary step of formally requesting the Assembly to pursue legal punishment for false testimony . By the end of Dec. 30, what had begun as a cybersecurity failure had morphed into a showdown between South Korea’s most powerful intelligence body and one of its biggest corporations – with each essentially accusing the other of lying.

Conflicting Claims: Did the NIS Gag Coupang from Calling the Cops?

At the heart of the dispute are directly conflicting accounts from Coupang and the NIS about who directed the breach response – and whether the NIS instructed Coupang not to involve law enforcement. The key point of contention is this: Coupang insists it acted under explicit guidance from government intelligence authorities, whereas the NIS claims it never told Coupang what to do. The truth has major implications, because if Coupang really received orders to keep police out of the loop, it suggests a deliberate cover-up or unauthorized intervention by the spy agency.

Coupang’s Story: From the company’s perspective, it was following orders in the chaotic days after discovering the breach. In public statements and testimony, Coupang has emphasized that it did not unilaterally conduct an internal probe, but rather coordinated every step with government instructions. For example, a Coupang press release on Dec. 26 flatly stated: “Unnecessary anxiety has surfaced as false claims of [Coupang] carrying out its own investigation without the government’s supervision are continuously made. As this data leak incident has caused great concern to the public, we would like to clarify the facts about the process of cooperation with the government.” The company then laid out its timeline showing how “the government suggested” contacting the suspect on Dec. 9, after which Coupang met the ex-employee, retrieved devices, and “submitted them to the governmental authorities”  . Crucially, Coupang says the NIS explicitly directed or ordered these actions: Rogers testified that “the agency instructed us, and we did what [it] told us to do”, describing multiple occasions where Coupang’s team was asked by NIS officials to engage the suspect and gather evidence  . According to Rogers, Coupang initially did not want to confront the suspected hacker directly – a task normally reserved for law enforcement – but “the [intelligence] agency repeatedly asked us to contact the suspect,” effectively turning that request into an order . He even told lawmakers that he understood such “requests for cooperation” from a government agency to be binding under Korean law, implying Coupang felt it had no choice but to comply .

Most significantly, Coupang’s timeline indicates that the company refrained from alerting the police until given the green light by the NIS. The phrasing that “the government allowed Coupang to submit evidence and testimonies to the police on Sunday [Dec. 21]” is telling . It strongly suggests that Coupang was instructed by the NIS to keep the matter within a small circle and hold off on involving the National Police Agency until the NIS had wrapped up its part. Indeed, the Seoul police later revealed they knew nothing of Coupang’s independent suspect chase until the company handed over the devices on Dec. 21, confirming “they were not informed” of any internal investigation beforehand . To outside observers, this lends credence to Coupang’s claim that it was acting under someone else’s direction – it would be highly risky (and arguably improper) for a company to delay informing law enforcement of a massive crime unless a powerful authority had told them to do so. Coupang maintains it was trying to help authorities quietly resolve the breach: by retrieving all stolen data and hardware, and even obtaining a confession from the perpetrator, before the situation went public or got worse  . In Coupang’s view, they were invited by the government to do a “covert op” and succeeded – recovering all leaked data and preventing further harm – only to be unfairly accused later of going rogue.

NIS’s Story: The National Intelligence Service vigorously denies that it ever directed Coupang to do anything beyond provide information. As soon as Rogers aired his version at the hearing, the NIS fired back that his statements were “not true at all” . The agency insists it never ordered or authorized Coupang to investigate independently, and had “never ordered, instructed nor permitted any actions by Coupang” aside from requesting cooperation and data . From the NIS’s standpoint, they merely assisted in a national security-related inquiry (since a foreign actor and massive data trove were involved) and asked Coupang to share whatever evidence it had – nothing more.

Specifically, on the flashpoint issue of contacting the suspect: the NIS states that it did not instruct Coupang to approach the hacker, but rather “stressed several times that Coupang should make the final decision” on whether to meet the individual . In other words, NIS officials might have told Coupang about the suspect’s likely whereabouts or identity and said “it’s up to you if you engage him,” perhaps implying they should, but never formally ordering it. This is a subtle but important distinction – the NIS is drawing a line between giving a nudge and issuing a directive. The agency also highlights that Coupang had already made a forensic copy of the suspect’s hard drive on Dec. 15, two days before the NIS even made contact on Dec. 17 . This point is used by NIS to argue that Coupang was operating on its own initiative initially; essentially, that Coupang’s tech team was already knee-deep in an internal probe and imaging drives without any instruction (and possibly without informing authorities immediately). The NIS claims it didn’t even know Coupang had that hard drive data until the Dec. 17 meeting . As for the handling of evidence copies, Rogers had alleged that the NIS kept a copy of the suspect’s drive image and provided another copy to Coupang while giving the original to police . The NIS flatly dismissed Rogers’s account as false – asserting it never possessed any copied version of the drive to distribute in the first place . The agency has been adamant that it simply doesn’t have the legal mandate to run domestic investigations or tell companies how to conduct theirs, and that Rogers’s portrayal of events is a distortion that “undermines the credibility” of a state institution  .

Finally, on the crux of police notification, the NIS has been a bit more circumspect. It has not explicitly admitted to telling Coupang “don’t go to the police,” but critics note that by omission, the NIS effectively cut out law enforcement until the end. The agency hasn’t provided a clear explanation of how and why the police were sidelined for so long. When pressed in public about this, NIS officials simply reiterate that no formal orders were given and that Coupang ostensibly acted on its own judgments . That leaves a noticeable gap in the narrative: if neither NIS nor police directed the breach response in early December, was Coupang truly acting alone? The NIS’s silence on what “advice” it did give (while denying issuing commands) has raised eyebrows. Even one Korean news report noted the NIS “did not elaborate on what views or advice it had presented to Coupang on contacting the leaker or securing a hard drive,” only insisting that any actual orders are “not true at all” .

In summary, the conflict boils down to semantics and credibility. Coupang says the NIS asked/instructed it to do X, Y, and Z – which Coupang interpreted as marching orders from a government authority. The NIS says it merely suggested/requested cooperation and left decisions up to Coupang – and that Coupang perhaps overzealously went off on its own tangent. The most damning claim from Coupang’s side is that the NIS told them to hold off involving the police, whether implicitly or explicitly. While the NIS won’t confirm giving such a directive, the timeline of events (police being looped in only after everything was wrapped up) strongly implies some agreement to keep the operation quiet. It’s extremely unlikely Coupang would delay notifying police for weeks without some form of instruction or assurance from officials. And indeed, police sources later warned that Coupang conducting an internal investigation without prompt police involvement was improper – a sign they were caught off guard and displeased . If Coupang’s claims are true, the NIS essentially ran a covert containment operation, prioritizing quick data recovery over transparency, whereas if the NIS’s claims are true, Coupang took liberties under the pretense of government approval.

The truth may lie in the gray area: the NIS might have strongly encouraged Coupang’s actions (thus de facto directing the probe) while never issuing formal “thou shalt not call the police” orders. Such wink-and-nod arrangements would let the NIS later say “we never ordered it.” This nuanced reality is hard to untangle, but the stakes are high – one of these parties is not telling the full story, and the South Korean public is keen to know who.

Harold Rogers: The Ethics Officer Turned Defiant Executive

The face of Coupang throughout this saga has been Harold Rogers, the acting CEO of Coupang Korea. Rogers is an American attorney by background – he has served as Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) and General Counsel of Coupang’s U.S.-based parent company . In effect, he was in charge of the company’s legal compliance and administrative oversight, a role that typically includes upholding ethics and transparency. That made Rogers’s confrontational and, at times, evasive conduct during the investigations all the more striking. Lawmakers expected a cooperative, contrite stance; instead, Rogers sparred with them, carefully guarded information, and appeared to prioritize legal positioning over full accountability.

Past Roles and Experience: Prior to being thrust into the interim CEO spot, Rogers was not a public-facing figure in Korea. Insiders describe him as part of Coupang’s top leadership circle that operates from the U.S. and largely comprises non-Koreans . In fact, over half of Coupang’s executive team is American, including founder Bom Kim (a Korean-American), the CFO, CISO, and Rogers himself . Rogers’s professional background as general counsel meant he often dealt with ethics, risk management, and regulatory compliance. He presumably helped craft Coupang’s responses to prior issues – for instance, labor disputes or safety controversies that have occasionally troubled the company (Coupang has faced criticism for worker conditions in its warehouses and delivery operations). However, Rogers mostly stayed behind the scenes until this breach propelled him forward. When CEO Park resigned amid the fallout , Rogers was parachuted in to stabilize the ship in Korea. His appointment was meant to signal a serious, reformist approach – the company literally put its chief legal officer in charge of cleaning up a mess with legal and ethical dimensions.

Involvement in Past Controversies: Though not well-known to the Korean public before, Rogers has now been linked to several Coupang controversies through the omnibus parliamentary hearings. The Dec. 30 joint hearing, for example, wasn’t limited to the data leak – lawmakers also questioned him about “unfair trade practices and labor conditions”, including allegations that overwork at Coupang led to employee deaths . These issues, while tangential to the breach, became part of Rogers’s purview as he fielded questions on how the company treats its merchants, whether it engages in monopolistic tactics, and its safety record. One flashpoint was Coupang’s customer compensation plan for the breach: lawmakers lambasted the 50,000 won voucher offer as a cynical marketing ploy (since most of the credit was in categories like luxury goods or travel that would compel customers to spend more)  . Rogers was forced to defend this plan, calling it “unprecedented” in scale and essentially ruling out any additional restitution . At another point, Rep. Kim Woo-young suggested the voucher scheme might even violate Korea’s fair trade laws by tying compensation to spending on Coupang’s services – noting that in the U.S., coupon-based settlements have been deemed illegal in class-action cases . Rogers, in turn, argued that those U.S. cases involved litigation outcomes whereas Coupang’s was a voluntary offering, disputing the comparison . This back-and-forth illustrated Rogers’s style: careful, lawyerly parsing of objections, which some lawmakers took as hairsplitting. It also showed him navigating prior ethical criticisms of Coupang (like consumer fairness and labor issues) in addition to the breach itself.

Evasive Testimony and Clashes with Lawmakers: Rogers has drawn sharp criticism for what Korean legislators perceive as an arrogant and evasive attitude. A vivid example came during the December 17 hearing (the one Bom Kim skipped, leaving Rogers as the top witness). From the outset, Rep. Kim Woo-young asked Rogers to state his name, phone number, home address, and email for the record  . The intent behind this unusual line of questioning was quickly apparent: as Rogers hesitated, Rep. Kim pounced on the irony. Rogers politely refused to disclose his personal phone number and address, saying “that’s private information that we don’t share.”   He similarly declined to give his email, citing privacy. Kim then pointedly noted the inconsistency – here was Coupang’s representative unwilling to share even basic personal details because they’re sensitive, yet earlier Rogers had seemed to downplay the severity of a breach that exposed precisely such personal data for millions of users  . In that same hearing, Rogers had argued that under U.S. regulations the leaked data (names, addresses, phone numbers, etc.) wouldn’t be considered “highly sensitive” – implying the breach might not even trigger mandatory disclosure in the U.S. because it wasn’t financial or health data . To Korean lawmakers, this stance was tone-deaf. Kim Woo-young retorted that U.S. privacy laws like the California Consumer Privacy Act do classify things like names and addresses as personal identifiers requiring protection . He then delivered a scathing line: “It is beyond dismay that a company whose representative refuses to reveal even his own phone number or address – because they are serious personal information – claims there was no significant impact, even though such data belonging to 33.7 million people was exposed.”  The exchange went viral in Korean media. It painted Rogers as someone hiding behind legal technicalities (U.S. vs Korean law definitions) and unwilling to personally stand by the implications of his statements. The lawmakers’ broader point was that Coupang – possibly under Rogers’s counsel – had initially tried to minimize the breach’s gravity, yet Rogers himself clearly understood the value of privacy when it came to his information. This episode made Rogers a target of public ire, with some calling his behavior “brazen” or lacking sincerity.

Another contentious moment was Rogers’s insistence on using his own interpreter in the National Assembly hearings. During the Dec. 30 joint hearing, the Assembly had provided a simultaneous interpretation service (Korean-English) for Rogers, who is not a native Korean speaker . However, Rogers brought along a personal interpreter and refused to use the official setup, saying “I have my interpreter,” and even boasting that his interpreter had U.N. experience . When the committee chair, Rep. Choi Min-hee, noticed discrepancies in the translation of Rogers’s answers, she grew alarmed. She caught Rogers’s interpreter rendering a phrase like “lowest rate” as “relatively low,” altering the nuance . “That’s incorrect… That kind of translation is unacceptable,” Choi snapped, accusing the private interpreter of paraphrasing and potentially softening Rogers’s words  . Choi demanded Rogers use the official earpiece, stating that at a previous hearing his interpreter had “paraphrased core parts” of his testimony . Another lawmaker chimed in, “If you respect the National Assembly of Korea, wear the simultaneous interpretation device.”   The scene devolved into a shouting match, with Rogers calling the request “highly irregular” and trying to protest, only to be overruled . Eventually, Rogers relented – he awkwardly wore the official translation headset in one ear while still listening to his own interpreter in the other ear for the remainder of the session . This peculiar standoff left a bad impression. Many observers saw it as Rogers attempting to control the narrative by filtering his statements through a translator on his payroll, which in turn made lawmakers suspect he was being less than forthright. It became a symbol of how the hearings often drifted into procedural tussles and grandstanding rather than purely focusing on facts of the breach.

By the end of December, Harold Rogers’s image in Korea had shifted from a low-profile legal executive to a somewhat controversial figure. Critics accuse him of “selective cooperation” – complying just enough to meet legal obligations (like the SEC filing) but resisting full transparency with Korean authorities and legislators. His measured, lawyerly answers and instances of non-compliance (like withholding personal info or initially defying the interpreter rules) were viewed as evasive. Lawmakers from both the ruling and opposition parties took turns rebuking him. Even simple questions turned heated; at one point, a frustrated Rep. hurled a remark about foreign executives not understanding Korean social responsibility, implicitly criticizing Rogers’s approach . To be fair, Rogers was navigating a minefield: balancing duties to U.S. investors, legal exposure from multiple lawsuits, and a highly charged Korean political environment. But his emphasis on what is “required under U.S. law”  and what is “not a violation” in the U.S., repeated during hearings, fed a perception that Coupang’s leadership (largely U.S.-based) was tone-deaf to Korean public sentiment and regulation . An anonymous Coupang insider even told local media, “What Coupang fears most is its U.S. investors… If you rank priorities, No. 1 is the U.S. market, and No. 2 is customer attrition [in Korea].”  That mentality, rightly or wrongly, was pinned on Rogers and his fellow expat executives. In short, Harold Rogers – a man whose career has been built on ethics and compliance roles – found himself accused of being unethical and non-compliant in the eyes of Korean lawmakers. It is a dramatic reversal that underscores the cultural and governance tensions underlying this incident.

The NIS’s Record of Overreach and Scandal

To fully grasp why the NIS-Coupang clash has struck a nerve, one must understand the historical baggage the National Intelligence Service carries in South Korea. The NIS (formerly known as the KCIA under military rule) has a long and checkered history of overstepping legal boundaries, especially in domestic affairs. South Koreans are acutely aware of past NIS abuses – unlawful surveillance of civilians, political meddling, even evidence fabrication – and this context makes any hint of NIS impropriety in the Coupang case especially explosive.

Election Meddling and Political Interference: Perhaps the most notorious example is the 2012 NIS public opinion manipulation scandal. In that incident, NIS agents were found to have conducted an illicit online smear campaign to sway the 2012 presidential election. They posted thousands of comments and social media posts slandering liberal opposition candidates and praising the conservative candidate, Park Geun-hye  . At the time, Park was running against Moon Jae-in (who is now known as a former president), and the NIS – under director Won Sei-hoon – allegedly portrayed Moon and other liberals as being “soft” on North Korea in order to aid Park’s chances  . After the election (which Park won by a narrow margin), the truth came out: Won Sei-hoon was indicted and eventually convicted for orchestrating this illegal cyber operation that violated election laws  . Prosecutors revealed that Won had ordered NIS cyber-warfare teams to flood online forums with pro-government opinions and suppress dissenting views, in what amounted to a state-sponsored disinformation campaign  . The scandal was so serious it nearly led to the impeachment of Korea’s justice minister at the time for trying to influence the investigation . In 2017, an internal NIS task force belatedly acknowledged the agency’s wrongdoing, admitting that its agents had “attempted to sway public opinion using internet trolls and social media” to keep conservatives in power  . It also came out that the NIS had been active in domestic politics even earlier – evidence showed that under the previous president (Lee Myung-bak), the NIS had systematically orchestrated activities of certain conservative civic groups, funding and directing right-wing organizations to hold rallies and spread propaganda supportive of the government . These revelations cemented the NIS’s image as a shadowy force meddling where it shouldn’t: instead of focusing on external security threats, it was policing public opinion at home and propping up the ruling party’s agenda. The legacy of these events is profound: in late 2020, South Korea’s legislature passed reforms explicitly banning the NIS from any involvement in domestic politics and transferring its domestic investigative powers (like counter-espionage) to the police . In short, there is now a legal mandate that the NIS stay out of internal affairs – a direct response to its prior overreach.

Unlawful Surveillance and Civil Liberties Violations: The NIS and its predecessors have also been embroiled in surveillance scandals. During the authoritarian decades (1960s–80s), the KCIA/NIS was infamous for spying on and suppressing dissidents, student activists, religious leaders, and journalists. While South Korea democratized in 1987, elements of that old behavior lingered. For instance, in the 2000s, reports emerged that the NIS had maintained files on civilians and possibly wiretapped conversations of politicians and businessmen (one high-profile case involved leaked “X-files” of illegal eavesdropping, which caused an uproar). The Al Jazeera columnist Andrei Lankov summed it up wryly: “the NIS is still basically the notorious KCIA, created by the military dictatorships in the 1960s – not so much to find North Korean spies, but to control and suppress local opposition.”  Even in the 2012 election scandal mentioned, part of the issue was the NIS’s “psychological warfare” unit operating inside the country to influence minds, which alarmed observers as an abuse of an intelligence unit meant for national security being used on citizens .

Another egregious case was the 2013 Seoul City spy fabrication incident. Here, the NIS targeted a Seoul city government employee, Mr. Yu Woo-sung, accusing him of being a North Korean spy. When the case against Yu started falling apart in court due to lack of evidence, the NIS presented what it claimed were Chinese immigration records proving Yu traveled to North Korea – essentially to bolster their charges . These documents purportedly showed Yu sneaking into the North multiple times. However, the Chinese authorities (unusually) alerted South Korea that those records were fake. In an embarrassing unravelling, it was exposed that the NIS had forged the documents. A recruited NIS informant (a Chinese national) testified that he was ordered by NIS handlers to fabricate the entry/exit records for Yu, under pressure to produce “evidence”  . In other words, the intelligence service tampered with judicial proceedings by creating false evidence – a textbook case of tampering with a criminal investigation. The fallout was swift: the NIS deputy director resigned and the NIS director at the time issued a public apology for the “apparent fabrication of evidence” in this espionage case  . President Park Geun-hye herself had to acknowledge the wrongdoing as the scandal grew. Commentators noted how this felt like a throwback to the bad old days when the security police would frame innocent people as spies to meet quotas or political goals . In Yu’s case, he was ultimately acquitted, and the incident reinforced the perception that NIS agents, imbued with excessive zeal and a “misguided sense of loyalty,” had crossed ethical and legal lines . As one analysis put it: the NIS likely “used all means at its disposal to make sure someone they considered a spy would not get off the hook. Since they could not produce sufficient evidence, they obviously decided to fabricate it.”  This kind of conduct – breaking the law to enforce the law, as it were – severely damaged the NIS’s credibility.

Interference in Civil Society: Beyond elections and spy-hunts, the NIS has been accused of inserting itself into various aspects of civil society. During the Park Geun-hye administration, for example, the NIS was implicated in maintaining a “blacklist” of cultural figures (artists, movie directors, etc.) who were critical of the government, resulting in those figures being denied arts funding and opportunities. Also, as noted earlier, during the Lee Myung-bak era, evidence later showed the NIS was secretly directing conservative civic groups and even organizing one-person protests and pamphleteering campaigns to support government policies . Essentially, the state intelligence apparatus was managing domestic opinion-shaping operations – something one might expect in an autocracy but not a modern democracy. Each revelation of such behavior has led to public outcry and promises of reform. The Moon Jae-in administration (2017–2022) in particular tried to rein in the NIS, culminating in the 2020 legislative reforms that aimed to restrict the agency to overseas intelligence and counter-terrorism, and keep it out of any domestic law enforcement or political activity .

Why It Matters Now: With that background, it’s easier to see why the Coupang-NIS confrontation resonates deeply. If indeed the NIS covertly instructed Coupang to investigate the breach internally and hush it up (even temporarily), many Koreans would see it as yet another instance of the NIS operating in the shadows beyond its authority. It would evoke memories of the agency’s past meddling and raise the question: Has the NIS really changed? The intelligence service’s reputation is such that its mere involvement can cast doubt on transparency. Opposition politicians and civil rights advocates have already seized on the Coupang case to argue that the NIS might be reverting to old habits of secrecy and overreach. The NIS’s aggressive response – publicly calling a corporate executive a liar and seeking his indictment for perjury   – also strikes some as heavy-handed, reinforcing the image of a powerful agency intolerant of dissent or criticism.

On the flip side, defenders of the NIS say that protecting the personal data of tens of millions is a national security matter (especially with a foreign suspect), and that the agency was right to get involved to contain the damage. However, even if well-intentioned, doing so behind closed doors and excluding the police would be seen as patronizing at best and authoritarian at worst. In South Korea’s democracy, the NIS must operate under strict oversight; any hint it is issuing orders to civilians or companies without legal clearance triggers alarm bells. The legacy of NIS scandals hangs over the current debate: it colors how the public interprets the NIS’s denials (with skepticism), and it raises the stakes for the government’s response (no one wants to be seen as giving the NIS a pass if it did break rules). In essence, the Coupang breach conflict has become a prism through which long-standing questions about the NIS’s role in a democratic society are being asked once again.

Political Theater at the National Assembly: Hearings and Reactions

The South Korean National Assembly’s response to the Coupang breach has been vigorous but, some argue, not entirely focused. Lawmakers have conducted multiple hearings, unleashing a barrage of criticism at both Coupang and government officials. While these hearings have shed light on the incident, they’ve also been marked by partisan splits, grandstanding, and questions that occasionally strayed from the core cybersecurity issue.

Parliamentary Hearings Unfold: The first major hearing came on December 17, 2025, under the Assembly’s Science, ICT, Broadcasting and Communications Committee . This session was notable for the absence of Coupang founder Bom Kim, which itself became a huge point of contention. Bom Kim’s failure to appear – he cited being overseas and busy running the global business – was taken as a grave insult. “Truly mocks the public,” scolded one lawmaker, comparing Bom Kim unfavorably to U.S. tech CEOs who have faced Congress . The committee formally decided to pursue legal action against Bom Kim for violating the National Assembly’s summons (in Korea, refusing a parliamentary summons can lead to fines or even jail) . This set a combative tone. In Bom’s stead, Harold Rogers was the highest-ranking Coupang representative present, and he took the brunt of lawmakers’ ire. Emotions ran high; lawmakers often shouted at Rogers, cutting him off, while Rogers in turn repeatedly begged to be allowed to finish his answers . At one juncture, the normally stoic Rogers even raised his voice and banged the desk, appearing visibly frustrated as he protested the government’s denials of instruction . The visual of a foreign executive in a heated exchange with elected officials made headlines (Chosun Ilbo ran a story titled “Coupang Rep Shouts, Taps Desk in Heated Hearing” to capture the drama).

That initial hearing also highlighted a partisan dynamic. The ruling party (the Democratic Party, DP, which confusingly is center-left despite its name) led the charge in castigating Coupang. DP lawmakers like Rep. Kim Young-bae accused Coupang of “consistently lying and refusing to submit requested documents.”  They also lambasted the compensation plan as inadequate and more like a sales promotion . The main opposition party (the conservative People Power Party, PPP), however, took a different tack: the PPP boycotted the Dec. 17 hearing and also a subsequent two-day joint hearing on Dec. 30-31 . Why? The PPP argued that a mere hearing was not enough – they pushed for a full-blown parliamentary investigation into the case, which would have broader powers. In essence, PPP legislators wanted a more formal inquiry (perhaps sensing an opportunity to scrutinize the government’s role, since the NIS ultimately reports to the President, who at this time was from the PPP’s own ranks, President Yoon Suk-yeol). The DP, controlling the committee, went ahead with the hearings anyway, so PPP members chose not to participate, calling them political theater. The result was that the hearings were dominated by DP and minor party lawmakers, without the presence of PPP members to provide balance or tougher questioning of government officials. This partisan rift slightly undermined the perception of the hearings – it became easier for critics to say the Dec. 30 joint hearing was more performative than substantive.

Joint Committee Hearing – Breadth vs. Depth: On December 30, the National Assembly convened an unprecedented joint hearing that pooled members from six different standing committees – including those dealing with science/ICT, national policy, labor, transport, budget, and even foreign affairs . Such a broad coalition signaled just how wide the scope of grievances with Coupang was. Lawmakers used the occasion to air long-standing concerns: the hearing’s agenda officially covered “Coupang’s personal data leak, unfair trade practices and labor conditions” . This Noah’s Ark of committees meant that questioning darted between disparate topics. In one moment Rogers was answering for the data breach; in the next, he was pressed about allegations of delivery drivers’ overwork and warehouse accidents (Coupang has faced scrutiny after several workers died, allegedly from overwork, in recent years). Then, questions would jump to whether Coupang abuses its market dominance to undercut small sellers (unfair trade). Some observers felt this diluted the focus on the data breach itself. However, legislators argued these issues were interlinked – painting a picture of a company that in their view has grown too big, too careless with safety and privacy, and too indifferent to Korean norms.

The joint hearing also drew criticism for some lawmakers’ showboating. We’ve discussed the interpreter fracas and the personal-information trap question, both instances where the hearing veered away from analyzing the breach and into scolding Rogers. While those incidents did highlight Rogers’s attitude, they also consumed time that could have been used to probe technical and procedural details of the breach response. For example, relatively little was discussed (at least in public session) about the specific cybersecurity lapse that allowed a former employee’s credentials to remain active and be exploited – a core issue for preventing future breaches. Instead, the hearing produced viral moments of confrontation: A lawmaker telling Rogers to respect Korea by wearing the interpreter earpiece ; another mocking the idea that Rogers thinks addresses aren’t sensitive data while guarding his own address . These clips played well on news broadcasts but arguably did not get to the bottom of the breach.

Even government officials in attendance were not spared. ICT Minister Bae Kyung-hoon had to repeatedly clarify the official stance that over 33 million records were compromised and that Coupang’s 3,000-user impact claim was unverified and premature  . He expressed “serious concern” about Coupang’s unilateral release of its probe results . Meanwhile, some opposition lawmakers (those who did attend) used their time to critique the government’s handling too – questioning how the NIS and police coordinated, and why the breach was not prevented given warning signs. However, the PPP’s absence on Dec. 30 meant there were fewer lawmakers inclined to grill the government side. The PPP instead held a press conference calling for an independent investigation, suggesting that the DP-led hearing was not asking tough questions about, for instance, the NIS’s conduct or the Science Ministry’s oversight.

One notable outcome of the hearings was a consensus (across parties) that Coupang had mishandled aspects of the aftermath and that stronger measures were needed. Lawmakers from the DP talked of imposing punitive damages and even revisiting Coupang’s market privileges if negligence was proven . The PPP, on its part, signaled it might support creating a special committee or investigative body. In a related move, by late December the Assembly was also debating tougher data protection legislation – spurred by the Coupang case and other recent big leaks (SK Telecom had a breach of 27 million users earlier in 2025, for instance, which led to a hefty fine) .

The interplay between legislators and Rogers grew increasingly combative. At one juncture in the Dec. 30 hearing, DP lawmaker Hwang Jung-a asked Rogers directly which government agency Coupang had coordinated with. When Rogers answered that it was the National Intelligence Service (publicly naming NIS, which until then wasn’t officially confirmed), there was a palpable reaction in the chamber  . Rogers even volunteered that he would provide the names of the NIS officials involved to the committee in private . That was a dramatic moment – essentially Rogers offering to blow the whistle on which intelligence officers were giving the orders. (It’s unclear if he subsequently did provide those names off-the-record, but the threat itself showed Rogers pushing back against the NIS’s denials). Lawmakers, while intrigued, quickly realized the sensitivity – this was verging into classified territory and could spark an institutional clash. The hearing pivoted to a closed-door session whenever specific sensitive details were discussed, according to Korean press reports.

Criticisms of Lawmakers: Korean media and the public offered mixed reviews of the National Assembly’s performance. On one hand, the Assembly was doing its job in holding a powerful company (and by extension government agencies) accountable in a public forum. These hearings were televised and drew significant public interest; they put both Coupang and the NIS on the spot. Rogers’s testimony under oath also created a formal record that can be used in any future legal actions (hence the perjury issue). On the other hand, commentators noted that some lawmakers seemed more interested in political point-scoring than in clarifying facts. The episode with Rogers’s personal data, while memorable, was seen by some as a cheap stunt that didn’t advance any policy discussion – it mainly served to embarrass the witness (which it certainly did). The interpreter controversy likewise, some felt, could have been handled more diplomatically off camera, but instead became a televised shouting match. An editorial in one Korean newspaper lamented that the hearings “devolved into a sideshow,” with lawmakers venting about Coupang’s foreign management or tangential issues, rather than drilling into how to prevent such breaches or improve inter-agency response. Indeed, much of the Q&A time was absorbed by issues like voucher compensation structures, market dominance, and even Rogers’s own employment history, which – while related to Coupang’s general practices – did not directly solve the mystery of who-said-what between NIS and Coupang.

Additionally, the partisan element meant that the Assembly’s response was somewhat fragmented. The DP-led committee formally censured Coupang for its executives’ no-shows and evasions . They talked of filing criminal complaints for perjury (which the NIS specifically requested regarding Rogers) and for Bom Kim’s absence  . Meanwhile, the PPP was calling for an entirely separate probe and criticizing the DP for not going hard enough on the government’s role. This suggests that when the dust settles, there may be a political tug-of-war over follow-up actions: e.g., whether to launch a special parliamentary investigation or to let law enforcement handle it from here.

In summary, the National Assembly’s hearings succeeded in airing the major issues in front of the public and extracting positions from Coupang and the government. They exposed the conflicting claims – Rogers basically accused the government of instructing a cover-up, and officials denied it – all on live record. But the hearings also illustrated the challenges of legislative oversight in such complex incidents. There was a degree of spectacle and lack of focus at times, which drew criticism that lawmakers “veered from the core issue.” Still, those core issues (data security, NIS’s proper role, corporate transparency) did come through amid the theatrics. For many Korean observers, seeing a U.S.-listed company being grilled and an intelligence agency being openly questioned in the Assembly was an encouraging sign of democratic accountability – even if the process was messy.

Who’s Telling the Truth? Parsing Coupang vs. NIS

After all the testimony, press releases, and political grandstanding, a pressing question remains: Who is more likely misrepresenting the facts – Coupang or the NIS? Both have doubled down on their version of events, and they can’t both be entirely right. Based on documentation and media investigations thus far, many analysts suspect that the truth is closer to Coupang’s account in some respects, albeit with nuance.

Consider the documented timeline and third-party statements. Coupang has provided a detailed timeline of its cooperation with the NIS  , which aligns with many known events (the suspect meeting, device handovers, etc.). Coupang even disclosed these facts in a filing to the U.S. SEC, which implies the company is confident enough in that narrative to report it to regulators (false statements there could carry legal penalties). The company’s claim that it delayed notifying the police at the government’s behest is indirectly supported by the police’s own statement that they had zero knowledge of Coupang’s internal investigation until Dec. 21 . If Coupang had truly been rogue, one might expect the company to at least quietly alert the police earlier to cover itself. The complete blackout toward law enforcement suggests an understanding that another authority was in charge initially. This strongly points to NIS involvement as Coupang describes.

Meanwhile, the NIS’s blanket denials raise some skepticism. The NIS’s statement that it “never ordered, instructed, nor permitted any actions by Coupang” besides requesting data  is carefully phrased. It’s essentially a legalistic defense – focusing on the words “order” and “instruct.” It’s quite possible the NIS did not issue any formal written orders. Instead, they might have phrased requests in a softer manner, which Coupang nonetheless interpreted as directives. For instance, if NIS agents told Coupang, “We need to resolve this quickly; perhaps you can talk to the suspect and get the data back,” a company like Coupang would likely treat that as an instruction, given the NIS’s clout. The NIS can then later say, “we never ordered them, they chose to do it.” This kind of plausible deniability is a hallmark of intelligence operations. The fact that the NIS also refused to detail what it actually said in those communications  is telling. If the NIS truly did nothing but ask for logs or data, one would think it could simply say so. Instead, it avoided answering how its “advice” was phrased.

Another inconsistency is the matter of when the NIS got involved. The NIS claims first formal contact on Dec. 17 . Yet Coupang’s timeline and statements indicate significant coordination starting well before that (e.g., Dec. 9 suggestion to meet suspect) . Could it be that someone from the NIS gave unofficial guidance around Dec. 9 without it being “formal contact”? Perhaps an intermediary or a phone call rather than a meeting. If so, the NIS might not count that as official instruction. But for Coupang, it was direction from the government. Here, Coupang’s specificity – naming dates and actions – gives its story weight. If any of those details were easy to disprove, presumably the government would have refuted them. Instead, the Ministry of Science and ICT and police have mostly taken issue with Coupang’s outcome claims (the “only 3,000 affected” part) , not with the process timeline.

The Perjury Question: The NIS pushing for Harold Rogers to be charged with perjury is a dramatic move, and it suggests the agency is extremely confident that it can prove Rogers lied under oath . However, pursuing perjury could backfire if evidence shows Rogers had reason to believe he was under instruction. Rogers, for his part, seemed remarkably willing to go on record with these assertions – even volunteering to provide names of NIS officials . It’s hard to imagine the interim CEO of a NYSE-listed company blatantly lying about government instructions in a public hearing without some documentation or correspondence to back it up. Coupang likely has internal records – emails, meeting notes, maybe even that Dec. 2 NIS letter – which could support Rogers’s testimony. If the issue escalates legally, those pieces might surface. The NIS’s call for perjury charges may be more of a muscle-flexing to defend its honor and dissuade others from making similar claims, rather than a signal it has ironclad proof Rogers lied.

Independent press coverage in Korea has hinted that multiple agencies were at odds behind the scenes. Leaks to media suggest the police felt sidelined and were unhappy with both Coupang and the NIS . The Ministry of Science, too, was clearly irked by Coupang’s unilateral SEC filing , but it also took a measured tone about “confirming facts” – possibly indicating it wasn’t fully briefed on NIS’s role initially. The Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) ordered Coupang to make customer notifications and corrections early on, implying it wasn’t in the loop on the secret retrieval operation. All of this points to an unusual chain-of-command where the normal actors (police, PIPC, Ministry) were partially circumvented. Such circumvention is more in line with NIS covert involvement than with Coupang spontaneously deciding to exclude regulators.

Coupang’s motivations also bear analysis. Why would Coupang risk doing a secret investigation without telling police? The generous interpretation is that Coupang panicked at the sheer scale of the breach and wanted to contain it quickly – perhaps thinking involving the NIS (which might have cyber expertise and overseas reach) was the fastest way to secure the data, while they worried the police would take longer or leak the news. It’s also possible Coupang hoped to avoid the bad PR of a public police investigation by fixing the problem quietly (a naive miscalculation, if so). But even if Coupang had selfish reasons, they still would likely need government cover to attempt such a thing. Otherwise, if caught, they’d face exactly the criticisms they’re getting now (doing a “self-investigation”). So from Coupang’s perspective, having NIS guidance would provide a shield – they could say, as they are saying now, “we were working with the government, not on our own.” Indeed, that is their defense.

Now, does the NIS have a motive to misrepresent? Certainly, it has institutional reputation to protect. Admitting “Yes, we told Coupang to hold off on calling the cops and handle it internally” would ignite a political firestorm (and possibly violate the 2020 reform law). It could be seen as the NIS prioritizing secrecy over rule of law. There could also be concerns about setting a precedent – the NIS doesn’t want to be known to interfere in private sector incidents, lest it discourage companies from reporting issues or cooperating normally. Moreover, if any laws were bent (for instance, not promptly reporting a data breach or a crime to law enforcement), the NIS would not want to be seen as having instructed that. Thus, the NIS has a strong incentive to frame this as Coupang’s own decision. The agency’s aggressive stance – publicly accusing Rogers of lying – might be an attempt to cast enough doubt that the public doesn’t automatically side with Coupang’s narrative.

Considering the press coverage and expert opinions: Korean media have largely reported the he-said-she-said without conclusively picking a side, but there’s an undercurrent of skepticism toward the NIS. After all, Rogers’s claim is extraordinary – a private company saying an intelligence agency told it how to handle a criminal matter – and ordinarily one might doubt a corporation trying to shift blame. But given the NIS’s track record, many commentators find Rogers’s story plausible. As one TV news pundit put it, “It sounds like the NIS wanted a quick resolution and didn’t trust the regular process, so they went to Coupang directly. That’s problematic, but not unbelievable.” On social media and in tech forums, some have pointed out that Coupang’s interests and the NIS’s interests aligned to some extent – both wanted the data leak contained and not widely known while they fixed it. So a theory is that the NIS informally told Coupang, “Take care of it and keep quiet for now,” and Coupang was all too eager to comply to save face. Then, once the job was done, the relationship frayed: the government felt Coupang jumped the gun in announcing the results (stealing the thunder and possibly downplaying the leak), and Coupang felt hung out to dry as officials refused to publicly acknowledge instructing them. This breakdown led to the finger-pointing we see now.

In weighing credibility, one might also consider Coupang’s risk calculus. Coupang is listed on the NYSE; making false claims about government instructions could attract scrutiny from U.S. regulators if it materially misled investors or impeded investigations. Rogers’s statements to the SEC and in the Assembly that the probe was done under government oversight indicate he was crafting a narrative not just for Korea but for investors too – basically “don’t worry, we didn’t bungle this alone, the government was involved.” If that were a lie, it’s a bold one with potential international repercussions. Conversely, the NIS’s statements were aimed at the domestic audience and are less likely to face an external audit, given the nature of intelligence work.

All things considered, Coupang’s claims appear to have more corroborating evidence (even if indirect), whereas the NIS’s blanket denials leave unanswered questions. It seems likely that the NIS is obscuring part of the truth – probably it did advise or even pressure Coupang to handle things quietly, but is now parsing language to deny it issued “orders.” Coupang may be technically overstating by calling those suggestions “orders,” but in practice, the effect was the same. In terms of misrepresentation, Coupang’s biggest potential fib would be the implication that it had no choice and was a passive participant; surely, Coupang also had its own motive to keep the breach under wraps initially (no company wants immediate public disclosure of a hack). But on the core factual question – did the NIS tell Coupang not to inform the police and to engage the suspect directly? – the available information tilts toward Yes, it probably did, albeit informally. That doesn’t exonerate Coupang, but it means the NIS may be more culpable in the controversial handling than it admits. This also aligns with the pattern from NIS’s past: operating in a gray zone and later denying wrongdoing once exposed.

Implications if the NIS Sidestepped Law Enforcement

If it is confirmed that the NIS instructed Coupang to bypass the police and conduct a clandestine investigation, the ramifications in South Korea would be significant on multiple levels – legal, political, and even economic. Such a revelation would effectively mean a government intelligence body interfered in what should have been a law enforcement process, raising urgent questions about inter-agency trust, democratic oversight, and the message this sends to businesses and investors.

Legal Consequences in Korea: First, consider the legality. South Korea has clear laws governing data breaches and incident response. Companies are typically required to report breaches to relevant authorities (like the PIPC and police) without delay. If the NIS told Coupang to hold off on involving the police, that could be seen as the NIS inducing a company to break reporting rules or at least to skate close to the line. Additionally, as noted earlier, legal reforms in 2020 explicitly curtail the NIS’s domestic role . The NIS is no longer supposed to be running domestic security investigations – those responsibilities (e.g., catching spies or handling major internal security incidents) were largely handed to police and prosecutors. A secret operation by the NIS in a domestic corporate crime might violate the spirit, if not the letter, of those reforms. This could trigger internal investigations by bodies like the National Intelligence Service Oversight Committee in the Assembly, or even by prosecutors if any law (such as abuse of authority or obstruction of justice) is deemed broken. Korea has mechanisms (though seldom used) to hold intelligence officials accountable – for instance, previous NIS chiefs have been prosecuted for illegal political interference . While it’s premature to talk about criminal charges, an inquiry might be launched to review the NIS’s conduct in the Coupang affair. If it found that NIS officers advised Coupang to conceal information or not follow legal procedures, disciplinary actions or even indictments could follow.

For Coupang, if it obeyed an NIS request to delay notifying authorities, it technically could be accused of violating the Personal Information Protection Act or other notification obligations. The Science Ministry already indicated it is investigating whether Coupang broke any data protection rules . If evidence shows Coupang willfully did a private deal with the NIS instead of promptly cooperating with the police, the company could face additional fines or penalties beyond those for the breach itself. (South Korea, in August, fined SK Telecom about 134 billion won for a breach of 27 million users ; Coupang’s breach affecting 33 million will likely incur a comparably large penalty or more.) If there’s an angle that Coupang impeded an investigation by not reporting it timely, that could aggravate regulatory action.

Inter-Agency Trust and Turf Wars: One big concern is how this affects trust between the National Police Agency and the National Intelligence Service. Historically, there’s been rivalry – the police have long wanted to take over domestic counter-espionage from the NIS, and as of 2024, they legally have that mandate. If the NIS effectively swooped in on what could be considered a domestic cybercrime case (even if involving a foreign perpetrator), the police leadership would be justifiably upset. It suggests NIS did not trust the police to handle it swiftly or discreetly. Going forward, the police might be much more cautious in sharing information with NIS or coordinating on cases, fearing they’ll be cut out. It could even spur the police to more loudly assert their jurisdiction. For example, the police might lobby the government to enforce stricter limits on NIS involvement in any future hacking incidents, or demand that any such involvement be done through formal channels with police oversight.

On the flip side, if the NIS feels it was publicly maligned (especially by Coupang’s claims) for doing what it saw as its duty, that could create reluctance within NIS to cooperate fully with other agencies in joint investigations. The NIS may retreat to a more secretive posture, which isn’t healthy for holistic cybersecurity defense. In the best case, this saga could prompt clearer protocols for inter-agency cooperation on cyber incidents – delineating when and how the NIS can assist (for instance, if a foreign actor or overseas data is involved) and how that must be done in tandem with police. Codifying that could prevent future confusion.

Democratic Oversight and Public Trust: Politically, an NIS misstep here would reinforce calls for stronger oversight of the intelligence apparatus. South Korea’s democracy has wrestled with how to keep the NIS in check, as detailed earlier. If the NIS is seen as having almost subverted due process (by telling Coupang not to go to law enforcement), it will alarm not just opposition politicians but also civil society groups. Lawmakers might call for hearings specifically targeting the NIS Director to testify (likely in a closed session, since intelligence matters are involved). They could demand to see the communications between NIS and Coupang – e.g., that December 2 letter, any emails, etc. If those reveal a directive to keep things quiet, expect a political uproar.

The National Assembly might take actions such as: passing a resolution condemning the NIS’s actions, establishing an independent fact-finding panel, or even appointing a special prosecutor to investigate (Korea has used special prosecutors for sensitive cases of government misconduct in the past, like the “Druking” online opinion manipulation case). There could also be personnel fallout – heads could roll at NIS if blame is assigned. Conversely, if the government (led by President Yoon’s administration) perceives that the NIS did nothing wrong, it may staunchly defend the agency, which could itself become a partisan flashpoint. The opposition DP might accuse the government of condoning NIS overreach, while the ruling conservatives might accuse Coupang (and by extension maybe the U.S. investors in it) of trying to undermine a national institution.

For the Korean public, trust is at stake. People entrust both the government and companies like Coupang with their personal data. Seeing an intelligence agency intervene secretly in a data breach could erode confidence that the authorities prioritize citizens’ rights over saving face. It also might discourage whistleblowers or others from coming forward if they suspect things will be hushed up. On the other hand, many Koreans are pragmatic – they may acknowledge that if the NIS helped get the data back, maybe that was a good outcome, but they’ll disapprove of the lack of transparency.

Implications for Businesses and Investors: If I’m a business leader in South Korea (or an investor in a Korean company), I’d be paying close attention. The idea that an intelligence service might step in during a cyber crisis and direct a private company’s response is unusual from a global perspective. Multinational companies in Korea might worry: If my company suffers a breach, will the NIS come knocking and ask me to handle it their way, potentially conflicting with my obligations in other jurisdictions? This could be concerning for foreign firms, as they have to navigate home-country laws too (for instance, EU companies have GDPR obligations to disclose breaches within 72 hours; they can’t just quietly comply with an NIS request to keep it silent).

For global investor sentiment, the Coupang incident is a test case. Coupang’s stock price did dip after the breach news (it fell ~17% in the weeks after the announcement) . Investors generally don’t like uncertainty, and this conflict with the NIS adds a layer of unpredictability to operating in Korea. It’s one thing to face regulatory fines for a data breach; it’s another to get embroiled with a spy agency. International funds might fear there are unseen political risks in Korean tech investments – will government agencies interfere in corporate affairs in opaque ways? Especially since Coupang is U.S.-listed, American investor reaction is important. In fact, a group of U.S. shareholders has already filed a class-action lawsuit alleging Coupang violated SEC rules by failing to disclose the breach promptly . If during that litigation it comes out that Coupang delayed disclosure because the NIS told it to, that introduces a geopolitical twist to what’s normally a straightforward securities matter. U.S. regulators (like the SEC) would be very interested in that, as it raises questions about foreign government influence on a U.S. market issuer’s disclosures.

From a comparative perspective, global companies might draw parallels to U.S. experiences. In the United States, if an analogous situation occurred – say the FBI or NSA quietly asking a company to hold off announcing a hack – it would be highly controversial. Generally, U.S. policy encourages companies to coordinate with law enforcement (like FBI) but not to hide breaches from the public or relevant authorities. In fact, U.S. breach notification laws (which exist in every state) require timely notice to affected individuals and sometimes to regulators. The idea of an intelligence agency telling a company “don’t tell the cops, fix it yourself” would probably result in congressional investigations and potentially legal consequences for any officials involved. The closest U.S. analogy might be if the NSA detects a foreign cyber-attack and works with a company to mitigate it quietly – even then, the FBI is usually brought in for the criminal side. So if Korea’s NIS did go solo, it could be perceived by foreign investors as evidence of a weaker institutional firewall between intelligence and civilian sectors in Korea. That might spook some investors, especially in sectors dealing with lots of personal data.

On the positive side, if handled properly, this incident could lead to strengthening Korea’s cybersecurity governance. It highlights the need for clear rules: for instance, should companies immediately inform a central authority like the PIPC or police, and then that authority coordinates with NIS if needed, rather than NIS going directly to the company? South Korea might institute a clearer protocol where any NIS involvement in a domestic breach is done through a joint task force from the start, to avoid these controversies. If investors see Korea learning and updating its frameworks, they might be reassured that the environment is maturing.

International Ramifications: There’s also an international relations angle: a significant portion of Coupang’s stock is held by foreign investors (SoftBank from Japan, American funds, etc.), and the suspect in the breach is Chinese. If the NIS took charge, it might have been partly due to the China aspect – intelligence agencies often get involved when an incident crosses borders or involves foreign actors. Should evidence arise that the data (33 million accounts) might have been targeted for espionage or by a state-linked hacker, the NIS would justify its role as protecting national security. However, if it’s just a rogue ex-employee seeking profit, then it’s more a criminal matter. The distinction matters for how much leeway the NIS is given. Legally, NIS handles national security threats, not ordinary crimes. A disgruntled former staffer stealing data to possibly sell – is that national security, or just crime? Arguably just crime. Unless there’s more to the story (e.g., the data was being sold to a foreign power or something), the NIS might have overstepped. Politically, Korea’s opposition may ask if the administration used the NIS to try to manage a PR problem quietly because of Coupang’s economic importance (Coupang is a major employer and a showpiece of “Korean Unicorn” success). That kind of allegation – that the NIS helped a big company save face – would look bad, suggesting collusion between big government and big business.

For democracy and transparency advocates, a key ramification is reinforcing the principle that no agency is above scrutiny. If the NIS did interfere improperly, the hope is that democratic institutions will correct it – either via parliamentary oversight or legal means. South Korea has progressed a long way from its authoritarian past; handling this episode correctly (acknowledging and rectifying any NIS missteps) would further solidify the rule of law. Conversely, if it’s swept under the rug, it could breed cynicism.

In sum, confirming NIS’s role would likely lead to: increased oversight of NIS (at least in the short term), possibly new rules for cyber incident handling, some tension between agencies as they sort out boundaries, and a reputational hit that Korea’s institutions will need to work hard to repair to maintain the confidence of both citizens and investors. As one lawmaker aptly warned during the hearings, “This incident should be an opportunity to improve our systems… Coupang’s decision to announce unverified findings raises serious concern” . Implicit in that is also: the government’s behind-the-scenes decisions raise serious concern. The ultimate outcome could either be a case study in how not to handle a breach or, optimistically, a catalyst for sweeping improvements in cybersecurity governance and institutional transparency in South Korea.

Broader Implications: Cybersecurity, Transparency, and Corporate Responsibility

Stepping back, the Coupang-NIS saga holds broader lessons that extend beyond South Korea’s borders. In an era where data breaches are a global scourge, this case highlights the delicate balance between swift incident response and the imperatives of transparency and rule of law. American readers, in particular, may find in this episode echoes of debates in the United States around how government and corporations should collaborate (or not) when hackers strike.